|

Case Report

Metanephric adenoma managed with robotic partial nephrectomy: A case report

1 Department of Urology, Levine Cancer Institute/Atrium Health, Charlotte, NC, USA

2 Department of Pathology, Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, NC, USA

Address correspondence to:

Ornob P Roy

Department of Urology, Atrium Health, 1225 Harding Pl #3100, Charlotte, NC 28204,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100033Z15HH2023

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Holck HW, Hall ME, Weida C, Roy OP. Metanephric adenoma managed with robotic partial nephrectomy: A case report. J Case Rep Images Urol 2023;8(2):1–5.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Metanephric adenomas (MAs) are clinically uncommon, with less than 200 cases previously documented. Preoperatively, MAs are difficult to diagnose due to the similarity of imaging characteristics with renal cell carcinomas. Even though MAs are benign tumors, they require careful consideration and treatment. We report a case of a MA managed via active surveillance followed by partial nephrectomy.

Case Report: After presenting for abdominal pain, a 1.3 cm left renal mass was diagnosed in a 58-year-old woman. Active surveillance was initially used to manage the mass for 2 years, at which point she elected for robotic partial nephrectomy. Final histopathological diagnosis was MA.

Conclusion: Preoperative diagnosis of MA is difficult as it shares many characteristic similarities with renal cell carcinomas. It is important for Urologists to be aware of MA as a diagnostic possibility. As awareness and understanding of MA increase, and diagnostic strategies continue to improve, active surveillance strategies may be increasingly utilized in management. If surgical extirpation is ultimately required, partial nephrectomy is a successful and reasonable approach.

Keywords: Metanephric adenoma, Pathology, Renal mass

Introduction

Metanephric adenomas (MAs) are infrequently reported etiologies of small renal masses (SRMs). They account for only 0.2–1% of adult renal epithelial neoplasms, with only several hundred cases previously described within the literature [1]. Metanephric adenomas arise from metanephric cells and are associated with maturing nephroblastomas, or Wilm’s tumors (WTs). Reports have described them as being more common in women (2:1) and generally arising in adults age 50–70 [2], although there have been reports of pediatric MAs in children as young as 15 months [3]. Metanephric adenomas are benign and have a favorable prognosis [4]. These tumors, however, are difficult to distinguish on imaging from other malignant etiologies including WTs in children and renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) in adults. Therefore, most MAs are diagnosed postoperatively via histopathologic analysis.

As SRMs are frequently diagnosed incidentally on imaging, MAs are an important possibility and a diagnosis with which genitourinary physicians should be familiar. Here, we report a case of a 1.3 cm post-surgical, histopathologically diagnosed MA managed with partial nephrectomy.

Case Report

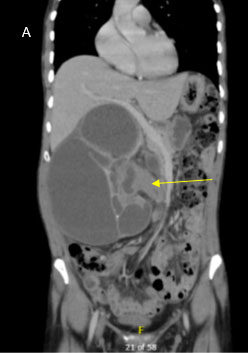

A 58-year-old woman with a past medical history notable for hypothyroidism presented for evaluation in March 2021, after incidental diagnosis of a 1.3 cm left renal mass on imaging obtained for workup of right upper quadrant abdominal pain in 2020. Comparison of her initial scan from 2020 to her more recent cross-sectional imaging showed an approximately 1.4 cm left lower pole partially exophytic lesion measuring 35 HU on noncontrasted phase with slight enhancement to 58 HU on the nephrogenic phase, which was overall stable in size (Figure 1). Staging imaging with chest X-ray did not demonstrate any evidence of metastatic disease and she had no systemic symptoms related to the mass. After a discussion of the options for management, including active surveillance, cryoablation, or partial nephrectomy, she initially elected for active surveillance. This lesion was monitored with minimal change in size or characteristics on serial computed tomography (CT) abdominal scans with and without contrast every six months until May 2022, at which point she elected to proceed with partial nephrectomy. Her imaging did not indicate growth over this 18 month period.

She was taken to the operating room on 7/29/2022 for a left robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy. Preoperative labs were obtained and indicated the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit was 14.0 g/dL and 41%, respectively. The patient was placed in the right lateral decubitus position, with the left side up and access was gained laparoscopically using a Veress needle. The robotic ports were placed under direct vision to the left of the patient’s midline. The descending colon was taken down along the white line of Toldt and the bowel was dissected medially until the left gonadal vein was identified. The ureter was elevated off the psoas and was dissected cranially toward the hilum. The hilum was isolated and the renal veins and arteries were freed of the surrounding tissue. Once this was completed, the perinephric fat was dissected off of the renal capsule. A yellowish-orange, partially exophytic lesion was identified arising from the left lower pole. An intraoperative ultrasound was used to identify the lesion of interest and to ensure there were no other suspicious lesions within the kidney prior to excision. The renal vein was then occluded using a bulldog clamp and the lesion was excised sharply with grossly negative margins. The vessels at the base of the resection bed were oversewn with absorbable suture. The base of the defect was then run closed and absorbable suture was used to close the capsule. Clamp time was 14 minutes. Total estimated blood loss was minimal and the patient was discharged home on post-operative day one without issues.

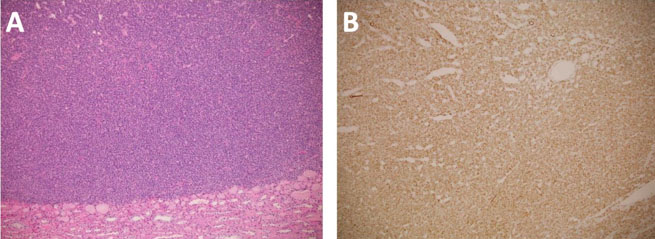

Surgical pathology demonstrated a well-circumscribed, exophytic mass measuring 2.0 × 1.7 × 1.7 cm, with pale tan/yellow soft tissue (Figure 2). Histology revealed a MA with negative margins. Immunohistochemical stains were performed and showed diffuse positive staining for Wilms’ tumor gene 1 (WT1) and negativity for cytokeratin 7, consistent with a MA (Figure 3).

The patient reported doing well at her 4-week postoperative appointment. Abdominal imaging was continued annually which has not indicated any recurrence to date.

Discussion

First described by Bove in 1979, MAs are a rare subtype of benign renal tumor that are typically found in adults [5]. Literature reviews suggest that most patients are clinically asymptomatic upon presentation, as was the case for our patient. Some patients, however, present with abdominal pain, hematuria, dysuria, fever, polycythemia, and a palpable mass [6],[7]. Additionally, around 12% of MA patients may also present with polycythemia, however, our patient had a hematocrit and hemoglobin within normal ranges [8]. Most MAs are diagnosed incidentally on radiologic imaging and are difficult to differentiate from other malignant etiologies of SRMs with imaging alone.

With conventional imaging, MAs typically have well-defined borders with a homogenous internal region. Larger tumors, however, have been described as containing hemorrhagic, necrotic components [9]. Studies have noted MAs typically have hypoechoic features on ultrasound (US) imaging, while some present as slightly hyperechoic or isochoic [9],[10]. Color doppler flow reveals limited vascularization of the tumor. This hypovascularization can be used to differentiate an MA from a hypervascular clear cell RCC. However, it is still necessary to consider other diagnoses with hypovascular characteristics including papillary RCC (pRCC), chromophobe RCC (ChRCC), lipid poor renal angiomyolipoma, and WTs.

In a study examining the US (contrast-enhanced and traditional) imaging features of several MAs, Zhu et al. found each of their 7 cases appeared as solid, well-delineated lesions with hypovascular characteristics [10]. Of note, pRCCs and ChRCCs have been described to exhibit similar characteristics including hypoenhancement and homogeneity [11].

Computed topography (CT) scans are another common modality of imaging on which MAs are frequently diagnosed. On CT, MAs have been described as well-defined, generally homogenous, and with an intact border. There are some inconsistencies in the literature regarding whether the majority of MAs appear isodense or hyperdense to surrounding renal tissue [12],[13],[14]. Case studies have suggested that the majority of these exhibit low levels of contrast attenuation on contrasted CT scan, although some MAs exhibit no measurable enhancement [15]. Our case was consistent with the majority of previously reported cases demonstrating slight enhancement with contrast.

Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans may offer an alternative imaging modality to assist in the differential diagnosis of MAs. Zhu et al. suggests that SPECT could be used to differentiate between benign and malignant tumors with benign tumors displaying a higher early relative uptake value than malignant tumors [16]. Current characterization of MAs with SPECT, however, is limited and therefore requires additional investigation [15].

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), MAs have exhibited hypointense characteristics on T1-weighted imaging and either iso- or slightly hyperintense features on T2-weighted imaging [17]. In a review of 8 cases, Yan et al. reported the MAs appeared isointense on both T1- and T2-weighted imaging [12]. Overall, the literature suggests MRIs do not further assist in making the differential diagnosis.

The lack of defining imaging characteristics can make MAs difficult to differentiate from pRCCs and is often what pushes physicians toward considering ablative or extirpative therapies, as was the case with our patient who was ultimately managed with a partial nephrectomy.

The gross pathologic findings in our patient are consistent with previously described MAs, including the presence of a well-defined border and a yellowish appearance (Figure 2). Calcification of MAs has been documented but was not noted in our specimen.

Given the challenges with making a definitive diagnosis with imaging, MAs are most often diagnosed on pathologic examination, generally after extirpative therapies. Histologic analysis of MAs shows epithelial cells with frequent psammomatous calcifications. These are derived from embryonic renal tissue in perilobar nephrogenic rests [18]. These morphologic traits are similar in nature to malignant WTs and RCC. In their growth cycle, MA cells express WT1 and cadherin 17 (CDH17) but do not express cytokeratin 7 (CK7), which in conjunction serve as immunohistochemical stains for histopathologic identification of the disease. Some reports have indicated MAs may have some focal expression of CK7 as well as CD57 [19]. Well differentiated, low grade pRCCs have intense reactivity to CK7 antibodies but lack expression of WT1 [20]. Higher grade pRCCs, however, may have little to no reactivity to CK7 and therefore may be difficult to differentiate from MAs [21]. Wilm’s tumors have a high expression of WT1 but lack expression of CK7 and CD57 [22]. These immunohistochemical stains ultimately serve to differentiate MAs from WTs and pRCCs. Our specimen stained positive for WT1, consistent with reports of most MAs, and negative for CK7, which is also consistent (Figure 2) [23]. Utilizing the increasing knowledge of the molecular characteristics of these tumors, there is the potential to diagnose them on renal mass biopsy. This depends on the clinical situation, location, and size of the mass.

Previously reported reviews have suggested that BRAF gene mutations are widely diagnosed in MAs, which may be a helpful clinical target in aiding preoperative diagnosis [2],[13]. Chan et al. reported the BRAF V600E mutation was present in all of their 11 samples [24]. This was supported by Wang et al. when they identified the same mutation in 66.7% of their MA specimens, but none of their pRCC samples. The mutation is rare in WTs [24],[25]. Trisomy 7 and 17 were also reported as rare in MAs and therefore could serve as another avenue of distinction from pRCCs [26].

Management with both partial nephrectomy and radical nephrectomy has previously been described [13]. To our knowledge, there is no standardized management strategy for these lesions, but given their benign nature we would propose that patients can be safely managed with partial nephrectomy, and possibly with active surveillance if a diagnosis is made prior to surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Here we describe a case of a MA successfully managed with robotic-assisted laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Metanephric adenoma is a diagnostic possibility that Urologists should be aware of and consider when undergoing evaluation of SRMs. As knowledge of these tumors increases, renal preservation strategies may be employed as a management option to potentially avoid over-treatment for benign metanephric adenomas.

REFERENCES

1.

Snyder ME, Bach A, Kattan MW, Raj GV, Reuter VE, Russo P. Incidence of benign lesions for clinically localized renal masses smaller than 7 cm in radiological diameter: Influence of sex. J Urol 2006;176(6 Pt 1):2391–5. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Rodríguez-Zarco E, Machuca-Aguado J, Macías-García L, Vallejo-Benítez A, Ríos-Martín JJ. Metanephric adenoma: Molecular study and review of the literature. Oncotarget 2022;13:387–92. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Hu S, Zhao Z, Wan Z, Bu W, Chen S, Lu Y. Chemotherapy combined with surgery in a case with metanephric adenoma. Front Pediatr 2022;10:847864. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

4.

Renshaw AA, Freyer DR, Hammers YA. Metastatic metanephric adenoma in a child. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24(4):570–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Bove KE, Bhathena D, Wyatt RJ, Lucas BA, Holland NH. Diffuse metanephric adenoma after in utero aspirin intoxication. A unique case of progressive renal failure. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1979;103(4):187–90.

[Pubmed]

6.

Obulareddy SJ, Xin J, Truskinovsky AM, Anderson JK, Franlin MJ, Dudek AZ. Metanephic adenoma of the kidney: An unusual diagnostic challenge. Rare Tumors 2010;2(2):e38. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

7.

Davis CJ Jr, Barton JH, Sesterhenn IA, Mostofi FK. Metanephric adenoma. Clinicopathological study of fifty patients. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19(10):1101–14. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

8.

Wang P, Tian Y, Xiao Y, Zhang Y, Sun FA, Tang K. A metanephric adenoma of the kidney associated with polycythemia: A case report. Oncol Lett 2016;11(1):352–4. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

9.

Jiang T, Li W, Lin D, Wang J, Liu F, Ding Z. Imaging features of metanephric adenoma and their pathological correlation. Clin Radiol 2019;74(5):408. e9–408.e17. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

10.

Zhu D, Zhu L, Wu J, et al. Metanephric adenoma: Association between the imaging features of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and clinicopathological characteristics. Gland Surg 2021;10(8):2490–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

11.

Xue LY, Lu Q, Huang BJ, Li CX, Yan LX, Wang WP. Differentiation of subtypes of renal cell carcinoma with contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2016;63(4):361–71. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

12.

Yan J, Cheng JL, Li CF, et al. The findings of CT and MRI in patients with metanephric adenoma. Diagn Pathol 2016;11(1):104. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

13.

Zhang L, Gao X, Li R, et al. Experience of diagnosis and management of metanephric adenoma: Retrospectively analysis of 10 cases and a literature review. Transl Androl Urol 2020;9(4):1661–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

14.

Fan H, Shao QQ, Li HZ, Xiao Y, Zhang YS. The clinical characteristics of metanephric adenoma: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(21):e3486. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

15.

Gong J, Dong A, Shao C. Metanephric adenoma mimicking renal cell carcinoma on 99mTc-MIBI SPECT/CT. Clin Nucl Med 2021;46(9):759–60. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

16.

Zhu H, Yang Bo, Dong A, et al. Dual-Pahse 99mTc-MIBI Spect/CT in the characterization of enhancing solid renal tumors: A single-institution study of 147 cases. Clin Nucl Med 2020;45(10):765–70. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

17.

Gohla G, Bongers MN, Kaufmann S, Kraus MS. Case report: MRI, CEUS, and CT imaging features of metanephric adenoma with histopathological correlation and literature review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12(9):2071. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

18.

Sarlos DP, Banyai D, Peterfi L, Szanto A, Kovacs G. Embryonal origin of metanephric adenoma and its differential diagnosis. Anticancer Res 2018;38(12):6663–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

19.

Padilha MM, Billis A, Allende D, Zhou M, Galluzzi-Magi C. Metanephric adenoma and solid variant of papillary renal cell carcinoma: Common and distinctive features. Histopathology 2013;62(6):941–53. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

20.

Kinney SN, Eble JN, Hes O, et al. Metanephric adenoma: The utility of immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analyses in differential diagnosis, including solid variant papillary renal cell carcinoma and epithelial-predominant nephroblastoma. Mod Pathol 2015;28(9):1236–48. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

21.

Kim M, Joo JW, Lee SJ, Cho YA, Park CK, Cho NH. Comprehensive immunoprofiles of renal cell carcinoma subtypes. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(3):602. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

22.

Muir TE, Cheville JC, Lager DJ. Metanephric adenoma, nephrogenic rests, and Wilms’ tumor: A histologic and immunophenotypic comparison. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25(10):1290–6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

23.

Li G, Tang Y, Zhang R, Song H, Zhang S, Niu Y. Adult metanephric adenoma presumed to be all benign? A clinical perspective. BMC Cancer 2015;15:310. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

24.

Chan E, Stohr BA, Croom NA, et al. Molecular characterisation of metanephric adenomas beyond BRAF: Genetic evidence for potential malignant evolution. Histopathology 2020;76(7):1084–90. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

25.

Dalpa E, Gourvas V, Soulitzis N, Spandidos DA. K-Ras, H-Ras, N-Ras and B-Raf mutation and expression analysis in Wilms tumors: Association with tumor growth. Med Oncol 2017;34(1):6. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

26.

Wang X, Shi SS, Yang WR, et al. Molecular features of metanephric adenoma and their values in differential diagnosis. [Article in Chinese]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 2017;46(1):38–42. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Author Contributions

Hailey W Holck - Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Mary E Hall - Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Carol Weida - Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ornob P Roy - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2023 Hailey W Holck et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.